Globalnews.kz continues to seek and post most interesting publications regarding Kazakhstan and its history. Below is a diligent abridged exposition of a complex research conducted by a group of international experts, namely CAROL KERVEN, SARAH ROBINSON and ROY BEHNKE from UK.

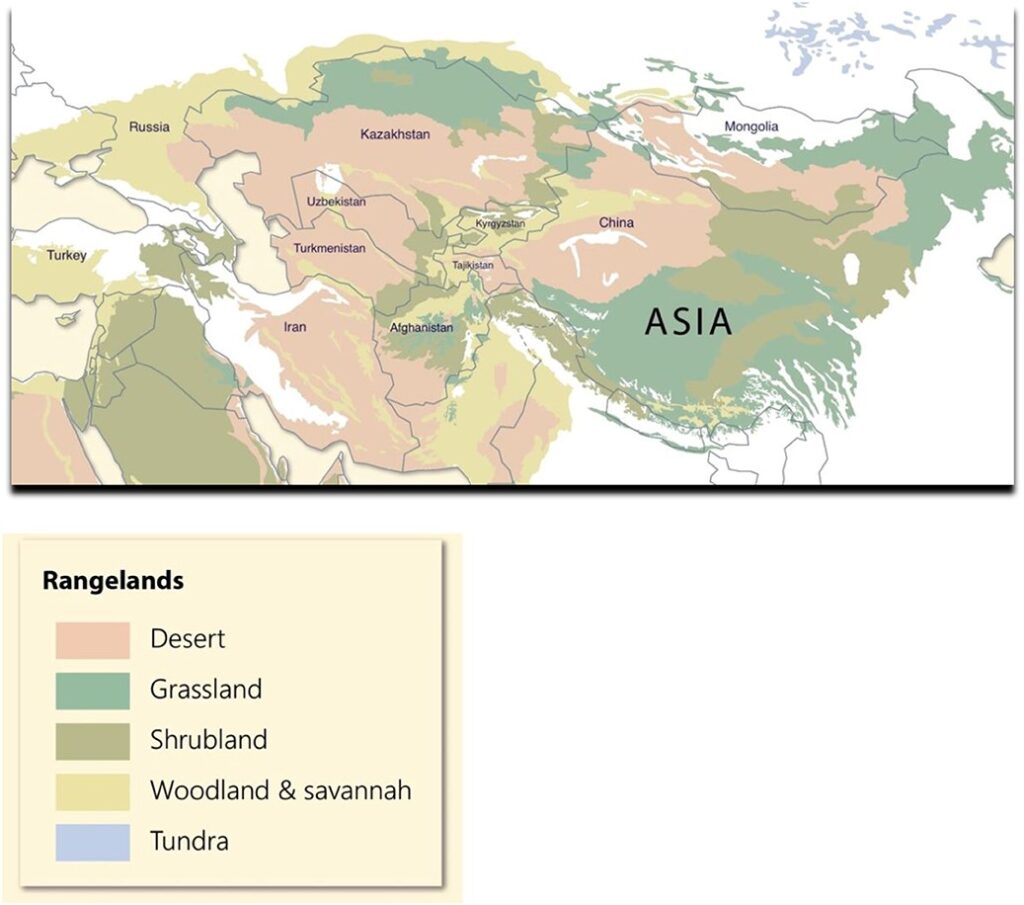

In the majestic realm of modern Kazakhstan, extending over 1.9 million square kilometers as recorded by FAOSTAT in the year of our Lord 2020, lies a vast expanse of pastureland, accounting for a remarkable 86% of the agricultural domain. This land, kissed by the sun and shaped by the wind, is predominantly semi-arid to arid, blessed with less than 300 millimeters of precipitation annually, often bestowed in the form of snow rather than rain.

These pastures, a tapestry of ecological splendor, stretch across diverse terrains. From the sandy deserts, where woody shrubs stand guard and ephemeral spring bulbs bloom, to the rolling plains adorned with short and long grass steppes, and reaching the alpine meadows that rise to the heavens at altitudes as high as 3,000 meters. Here, noble livestock graze under the summer sky, as chronicled by scholars Gilmanov in the year 1996, Asanov and others in 2003, and Van Veen and his compatriots in the same year.

The climate of this regal land is a testament to nature’s extremes — a realm of icy winters where the mercury plunges to -30C, and scorching summers where it soars to heights of 50C. A significant hallmark of these pastures is their reliance on the gift of irrigation, for without it, the art of arable agriculture would remain an elusive dream.

In the annals of archaeological lore, it is revealed that mobile pastoralists and their faithful livestock have been the stewards of these lands for no less than 5,000 years, a testament to the enduring bond between man and nature. This Eurasian region, as scholars Frachetti and others elucidated in 2012, was a cradle for the domestication of goats, sheep, horses, and the majestic Bactrian camels between 10.5 and 4 thousand years past.

Recent scholarly quests, uniting the wisdom of archaeologists, climate savants, and ecologists, have shed light on the intricate dance between nomadic migrations, settled farming, climate’s caprice, and the whispers of the environment over the last millennia. These revelations speak of how pastoralists, with varying degrees of wanderlust, harnessed the ever-shifting climatic tapestry to sustain their herds.

From time immemorial, these nomadic groups, guided by the rhythms of climate and the mosaic of vegetation, traversed ecozones with their livestock, moving great distances latitudinally, shorter spans altitudinally, or undertaking modest journeys complemented by the generous provision of fodder.

Archaeological excavations in Kazakhstan hint at a prehistoric era where pastoralist mobility mirrored the patterns observed in the ethnographic present — a dance of seasonal movements across known ecological stages of productivity, as poetically described by Frachetti in the year 2015.

The current floral and faunal biodiversity, along with the landscape’s character in the Eurasian rangelands, is a legacy of centuries of human interaction through mobile livestock husbandry, intertwined with the forces of climate change, technological advancements, and the evolution of socio-political structures. In this great historical migration of mixed herding and farming, it was the sheep that led the way between 5000 and 2000 BCE, as narrated by Frachetti and others in 2012.

This paper, set against such an archaeological backdrop, delves into the historical annals of the past two centuries to explore how pastoralist livestock management and land use in Kazakhstan have been sculpted by the hands of socio-political and economic change. It posits that the geographical diversity of Eurasia’s climate demanded specific social structures to effectively harness the bounty of the rangelands. The social fabric of extensive livestock management had to mirror the geographical scale of mobility dictated by both biotic and abiotic forces.

The present-day state of the Kazakh rangelands is a tapestry woven from the interactions between humans and livestock over millennia. Preserving this rich mosaic of rangeland diversity calls for the livestock-keepers to continue their grand operation at scale, as evidenced by the environmental impacts of recent declines in livestock mobility.

In this historical narrative, we trace the dynamic influence of humanity on the Kazakh rangelands over the past century. From the earliest written records, a chronology emerges of three national socio-political upheavals over the last 100 years, each casting ripples across the pastoral landscape. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Kazakh pastoralists embraced a pre-industrial nomadism, characterized by kinship-based units within a hierarchical political tapestry. The early 20th century witnessed these structures being supplanted by a collectivized socialist system under state stewardship. The late 20th century saw the dawn of a capitalist economy, where individual families harnessed private resources to sustain livestock mobility.

This century of transformation has left indelible marks on the rangeland ecology and the pastoralists’ economic, social, and cultural fabric. The conclusion ponders the future changes that might unfold as a result of the current institutional landscape and management practices.

From the annals of the earliest explorers to the insights of modern social scientists, the social tapestry of the Kazakh people has often been painted with the brush of «clans.» This review adopts this term, mindful of its layered and evolving meanings through history and across scholarly debates. The term «clan» has been interpreted and reinterpreted through the lenses of different historical periods, political ideologies, and ongoing academic discourse.

Russian accounts of Kazakh clans from the 18th century, later summarized in English works, offer a glimpse into the social organization of Kazakh nomadic movements with livestock. These sources generally concur that regular seasonal movements to graze livestock in mobile encampments were the domain of the aul, a co-residential group anchored by patrilineal kinship. The aul’s size and structure were fluid, shaped by ecological conditions, external threats, and internal dynamics, fluctuating in response to seasonal shifts, pasture conditions, and labor needs.

This discourse also intersects with the theme of social stratification and class formations among Kazakh livestock-keepers. Historical records, penned by geographers, administrators, ethnographers, and historians, provide diverse perspectives on Kazakh society. Yet, the true extent of class divisions in historical Kazakhstan remains a subject shrouded in mystery. Comparative studies with other pastoral societies suggest that cycles of livestock wealth and loss led to oscillating class structures among the Kazakhs, further complicated by patron-client relationships.

In the Tsarist period, starting in the late 1700s, Kazakh nomads managed their livestock by traversing ecological zones, seeking seasonally available grazing areas. These movements, undertaken by extended family groups in their auls, were dictated by the environment’s offerings of water and pasture, profoundly influencing the herd size and camp composition.

Thus unfolds the tale of the Kazakh rangelands, a narrative rich with the interplay of nature, culture, and history, painting a portrait of a land and its people, forever intertwined in the dance of survival and prosperity.

The photograph in question serves as a pivotal piece of the Turkestan Album, an extensive visual chronicle of Central Asia, crafted in the wake of Imperial Russia’s annexation of the region during the 1860s. This monumental endeavor was commissioned by General Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman (1818–1882), the inaugural governor-general of Russian Turkestan. The primary architect of this compendium was the esteemed Russian Orientalist Aleksandr L. Kun, with Nikolai V. Bogaevskii rendering vital assistance.

The aul, a cornerstone of this society, was a harmonious assembly of several conjugal families, all tracing their lineage to a common forefather, thus forming a patrilineage, as elucidated by Ohayon in 2005. Leadership within the aul was entrusted to the elder men, revered as aksakal – literally translating to “white beard”. These venerable figures bore the responsibility for safeguarding their people and the pasturelands under their stewardship, as detailed by Olcott in 1995. The elders held the prerogative to appoint an individual known as the bii, tasked with representing the clan in diplomatic engagements with other clans and auls. These gatherings, convened annually, were instrumental in determining the routes for the season’s migrations and in allocating access to winter pastures. The biis, perceived as lesser nobles, not only defended their group’s rights to pastures but also played a pivotal role in resolving disputes, as noted by Martin in 2001. Additionally, they represented lineage groups of Kazakh nomads in negotiating annual migratory paths between clans and also undertook military duties.

A network of groups, potentially comprising over a hundred auls, would migrate within a designated geographic zone, as Olcott highlighted in 1995. This grand scale of nomadic movement, orchestrated through kin-centric social units, began to face constraints when the Russian government exerted control over the northern pastures of the Kazakh nomadic pastoral tribes, fortified these lands, and opened them for colonization by Slavic peasants. This incursion, occurring in the 18th and 19th centuries, was identified by Kappeler in 2001 as a «decisive destabilizing factor for the Kazakhs.» The encroachment of Slavic peasant farming pushed the nomads to retreat southward to drier territories. For the Russian authorities, these lands were unclaimed expanses, yet for the Kazakh nomads, they were indispensable pastures, collectively owned by the ulus (clans) or other nomadic units, as Khodarkovsky articulated in 2002.

The Kazakhs, when requested by Russian frontier officials to pay fees for using these pastures and crossing rivers, were taken aback, expressing their belief that «The grass and water belong to Heaven and why should we pay any fees?» This sentiment reflects a profound dissonance between the perspectives of the Russian government and the Kazakh nomads regarding land ownership and use.

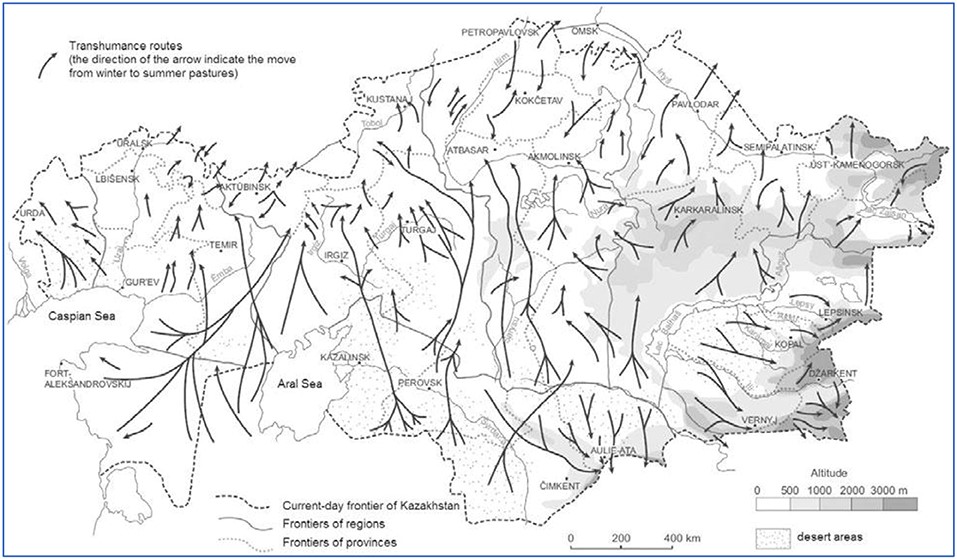

In the 19th century, Russian ethnographers and administrators documented a plethora of regional variations in nomadism and semi-nomadic pastoralism within what would later become Kazakhstan. This mode of pastoralist production was influenced by several key factors: terrain type (plains versus mountains), climate regime (from arid to wetter), water supplies (including rivers and groundwater), and associated pasture soils and vegetation, as detailed by Federovich in 1973, and further examined by Guirkinger and Aldashev in 2016. The plains-based nomadic economy relied on extensive migrations with grazing livestock, covering distances up to or exceeding 1,000 kilometers on a north-south axis throughout the year, spanning from the northern steppe to the semi-desert and desert regions in the south for overwintering. Semi-nomadic groups also existed, maintaining permanent winter quarters. The mountain-centered livestock production system was characterized by vertical transhumance, with settled winter bases in the valleys or semi-steppes surrounding the mountains, and transitions to upland alpine meadows during summer for pasturing, often covering over 100 kilometers between summer and winter pastures.

Picture above in the referenced work illustrates the seasonal movements of Kazakh nomads towards the close of the 19th century, drawing upon the insights of Kerven (2004) and Ferret (2014), and foundational knowledge from Federovich (1973). This epoch witnessed the crystallization of social distinctions within the nomadic communities, not only based on a family’s economic standing but also influenced by an aristocratic hierarchy that was genealogically calculated, as expounded in the detailed discussion by Martin (2001), which itself leans on earlier sources.

During the Tsarist era, the erstwhile aristocratic rulers, known as the White Bones, found themselves either co-opted or subdued. By the late 1800s, Russian administration had effectively diminished the large territorial and political influence wielded by the upper echelons of Kazakh aristocracy, including the bii, as noted by Wendelken (2000). Over time, the term ‘bii’ seemed to morph into ‘bai,’ a transition observed in works such as Olcott (1995). ‘Bai’ in Kazakh parlance refers to a wealthy individual, typically one who possesses a substantial number of livestock. This conflation of terms might have arisen as Russian administrators aimed to co-opt the bii, who were considered elites within the Kazakh social structure, a phenomenon discussed by Ohayon (2005) and Sneath (2007).

With the onset of sedentarization, as Kazakh nomads began establishing villages, the role of the bais (or bailar in Kazakh) as local leaders gained prominence. The Russian authorities, adopting a strategy of indirect rule, empowered and compensated these bailar to collect taxes and maintain social order on their behalf (Wendelken, 2000; Ohayon, 2005). As the bii accrued wealth through interactions with the Russians, they began to be identified as bais. The Russian settlement in northern regions disrupted traditional Kazakh migratory routes, thereby diminishing the broader patronage and defensive relationships that previously existed between auls and higher-level social entities, breaking up the large territories of political power within a hierarchical social system (Martin, 2001). Consequently, the Kazakhs’ reliance on their smaller aul groups intensified, leading to the emergence of a new social production system centered around the aul obshchina or “community,” characterized by communal land use and collective herding of livestock.

The latter part of the 19th century saw a reduction in the need for nomadic movement, as the influx of Russian settlers and traders in the north generated new markets for Kazakh livestock, especially cattle. In response, Kazakh pastoralists began to maintain larger herds of cattle alongside sheep in the northern steppe regions. However, cattle being less suited to long migrations needed additional feed to endure the harsh winters. This requirement led to an intensification of pastoralism, with the adoption of scythes enabling richer Kazakh nomads to harvest more hay for sustaining their livestock through the winters. This development reduced the need for longer migrations to warmer areas and allowed households to maintain larger herds (Kazakh Academy of Sciences, 1980; Matley, 1994b; Aldashev and Guirkinger, 2017). The increasing expropriation of pastures by the Russian administration for Slavic settlers further necessitated greater Kazakh sedentarization.

Commercialization brought about greater economic differentiation among Kazakh pastoralists, with livestock wealth becoming increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few bailar who had gained significant local political power. As Olcott (1995) observed, an ever-larger portion of the total herd came to be held by an ever-smaller number of individuals. However, as noted by Kerven (2003), even into the 1920s in northern Kazakhstan, social and economic patronage obligations persisted between richer and poorer related families within an aul. This meant that wealth was not confined to an individual but was more broadly distributed among families. Richer and senior males within a lineage held responsibility for decisions on livestock management, a fact corroborated by historical records (Ohayon, 2005). By the end of the 19th century, the average number of yurts in an aul had dwindled to four or five, with wealthier families possessing larger herds and flocks, and incorporating poorer individuals who performed basic tasks in exchange for their upkeep within the aul encampment (Ohayon, 2004).